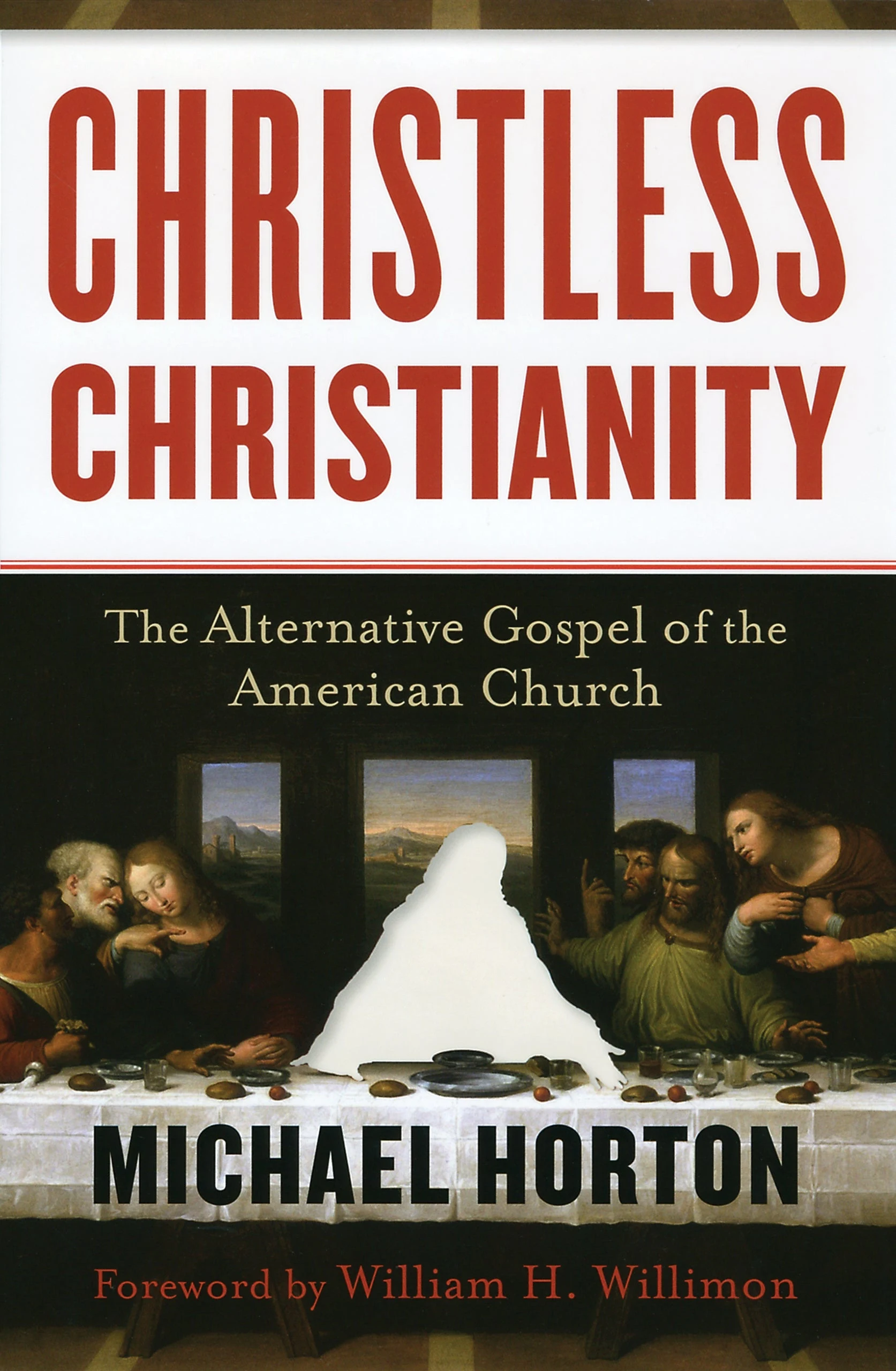

Book Review: Christless Christianity

In his recent book, Christless Christianity, Dr. Michael Horton has analyzed the problems that assail the contemporary evangelical church community. Leaning heavily upon the research of sociologists of religion such as James Davidson Hunter, and others, Horton has been able accurately to pin the tail on the evangelical donkey. This comes to the fore especially when he takes a cue from sociologist Christian Smith, who notes the pervasive presence in modern evangelicalism of a moralistic and therapeutic deism. Smith defines the characteristics of this contemporary form of deism by listing five of its assertions. First, God created the world. Second, God wants people to be good, nice, and fair to each other. Third, the central goal of life is to be happy and to feel good about oneself. Fourth, God does not need to be particularly involved in one's life, except when needed to resolve a problem. And last, good people go to heaven when they die.

Historic deism was a very brief blip on the radar of Christian history. Its appearance in American history was also short-lived; however, it happened to reach its zenith at a crucial juncture when the American republic was in its formative stages. The idea that God created the world but stepped out of the picture after setting the universe in motion was popular among many deists of the eighteenth century. The religious dimension of deism quickly passed from the scene, but its principal concepts did not go away. They are still deeply rooted in the collective psyche of American people.

The second great influence in modern evangelicalism comes from ancient Pelagianism. Pelagius in his dispute with Augustine of Hippo denied the reality and ramifications of any original or ancestral sin and argued that Adam's sin affected only Adam and no one else. Adam merely set a poor example for his descendants. Pelagius also argued that grace is not necessary for a person to live a perfect life. He admitted that grace was real and could facilitate godly lives but it was by no means a necessary precondition for it. He saw religion as being expressed strictly in obedience to the moral law.

Though Pelagianism was condemned by the church early on, it nevertheless did not go away. Weaker forms of it persisted in what was called semi-Pelagianism, which probably is the majority report among practicing evangelicals today. Pure Pelagianism saw a strong revival, as Horton notes, in the nineteenth century revivalistic methodologies of Charles Finney. Finney has emerged as an icon of modern evangelism despite the fact that he too denied original sin and its ramifications, as well as the doctrine of justification by faith alone and the substitutionary atonement of Christ. His basic religion was a call to righteous living based upon decisions made by the will unfettered by original sin.

The religious dimension of deism quickly passed from the scene, but its principal concepts did not go away.

Added to the mix of deism and Pelagianism is the contemporary revival of ancient Gnosticism. The Gnostics were called Gnostics because they were people who were “in the know.” They eschewed the function of the mind and rationality in achieving truth. Rather, truth was discovered through mystical insight and imaginative leaps of intuition. The anti-theological spirit of much of modern evangelicalism reflects this preference of intuition and imagination over the rational understanding of the Word of God. Most central to neo-Gnosticism, however, is the emphasis placed upon personal experience. Salvation is not rescue from sin, death, and the wrath of God and from His judgment because of our sin, but rather salvation is found in a personal experience of relationship, particularly a relationship with Jesus. But the Jesus with whom one has a personal relationship is far removed from the historical person by that name, whose deeds are recorded in the New Testament.

Horton observes that the spiritual bracelet fad, where the initials WWJD adorned the arms of devout people, indicating the message “What would Jesus do?” would be better served by a bracelet that had the initials WDJD—not WWJD—indicating the phrase “What did Jesus do?” It is the person and work of Christ that is the essence of the New Testament gospel. But in contemporary categories, the objectivity of the gospel has been all but been obscured by new approaches to religion.

Horton has always been interested in dealing with the relationship between law and gospel, and again he sees the confusion of law and gospel as having a deleterious impact on the church today. Obviously, when law and gospel are confused, the clarity of the law is lost and with it the clarity of the gospel. If there is no law that comes from a sovereign God, then there can be no real conviction of sin. And where there is no law, gospel is not necessary. And so the gospel is transformed into a message not of redemption from sin but into one of self-fulfillment. Horton thus spends considerable time looking at the ministry of Joel Osteen, a practitioner of the word of faith movement whose popularity has perhaps been unprecedented. Influenced both by Norman Vincent Peale and Robert Schuller, Osteen makes it clear that in his preaching, sin is not an issue. He is helping people to find personal levels of self-fulfillment. For him, salvation is prosperity and fulfillment here and now in this world.

In similar fashion, many in the emergent church movement have turned their backs on classical categories of the gospel and have substituted a different kind of salvation. For certain representatives of the emergent church, such as Brian McLaren, the gospel message is that we can have peace and justice here and now. Just as David Wells disturbed the leadership of modern evangelicals with his book No Place for Truth, so Horton picks up on the idea by showing the death of truth in the substitution of experience that is so widespread in the evangelical world today. The book is well written and is one that offers great insights to those who are scratching their heads and wondering: “What in the world is going on in the church today?”