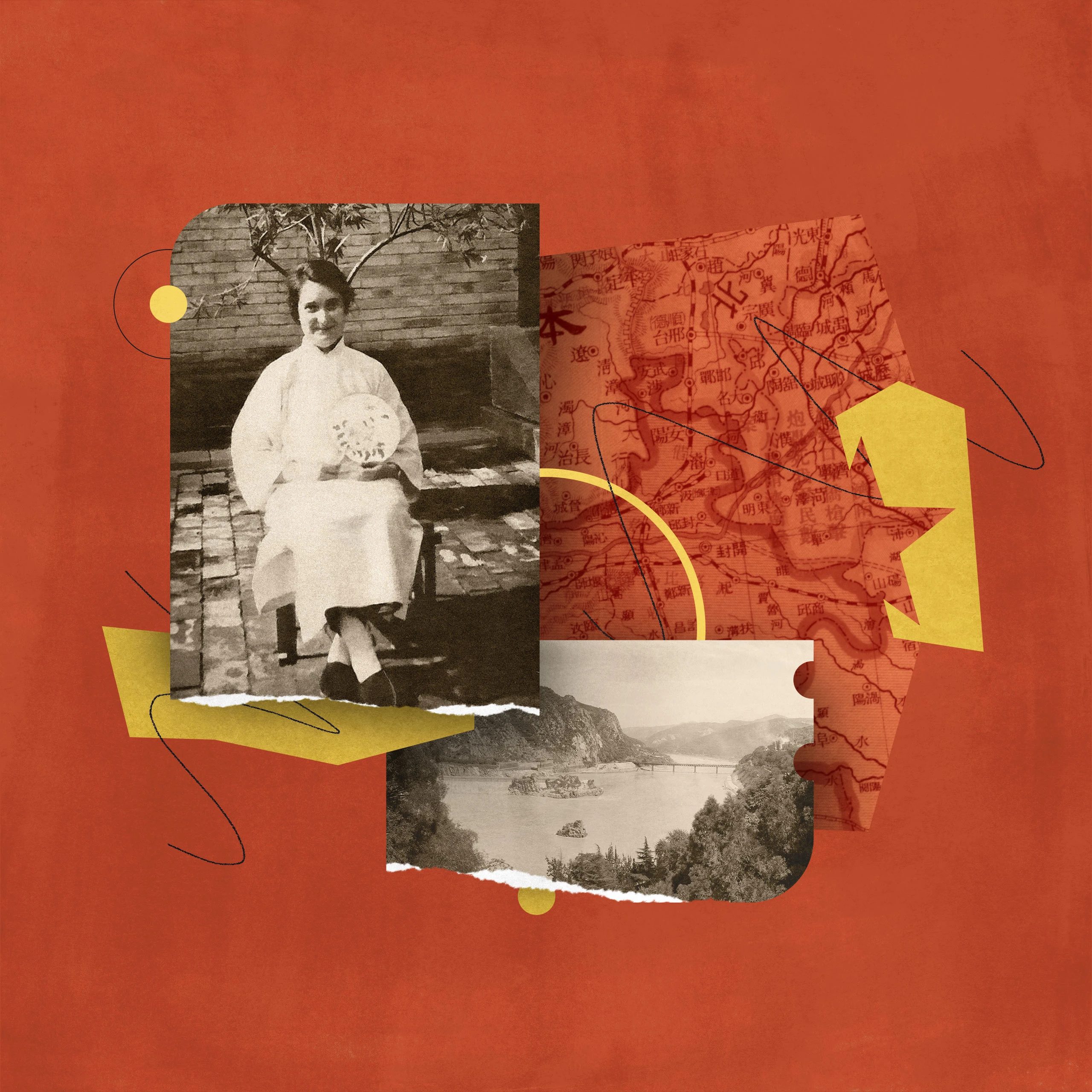

Who Was Gladys Aylward?

Gladys Aylward was a determined woman. Once she felt the call to the mission field, she refused to allow any excuses to hold her back. Although she appeared to lack the resources for mission work, God affirmed her calling and gave her many opportunities to overcome practical obstacles.

Early Life

Gladys was born in Edmonton, a town north of London, in 1902. Growing up in a churchgoing, working-class family, Gladys left school at the age of fourteen. She found that working as a parlor maid in the big London houses was more to her taste than school. The work was hard, but she enjoyed living the life of the rich vicariously.

One evening, Gladys, in her mid-twenties, went to a revival meeting. Unsure why she had chosen to attend, she found herself being challenged by the gospel. By the time she left the meeting, she had become a Christian. The focus of her life changed completely. She joined Young Life Campaign and spent her off days learning to share the good news of Jesus. Through one of their magazines, she learned about the many people in China who had never heard the gospel. Feeling the call to go, she presented herself as a candidate to the China Inland Mission in 1929. They accepted her into their training program despite her poor education and her being in her late twenties. However, after three months she was asked to leave because, even though she had excelled in the practical work, she had failed the classroom work. The Mission felt she could not be adequately prepared for the mission field.

Disappointed but undeterred, Gladys went back to working as a maid, determined to earn the money needed to travel to China. She asked God to clear the way for her, and He did. She managed to earn and be given enough fare money in one year instead of the three she had calculated. Friends and employers gave her necessary items such as clothing, a suitcase, and a small stove. Finally, missionary Jeannie Lawson had written the congregation asking for a young woman to help her mission work in Yangcheng in northern China.

To China

The train trip across Europe and Asia on her own in 1932 was fraught with danger, but God supplied strangers who took Gladys under their wing until she arrived at the border between Russia and China. War was raging between the two countries, and Gladys was caught in the middle. She was briefly arrested, questioned, and released, but she still couldn’t get to China. Then, a kind stranger got her passage on a ship to Japan, and from there she was able to continue.

Finally arriving at her destination, Gladys discovered that Jeannie Lawson’s mission was an inn for muleteers who stopped overnight on their trade routes. From the beginning, Jeannie and Gladys did not get on. Jeannie, a demanding elderly woman, put Gladys in charge of the mules instead of the people. Tempers flared when Gladys complained. After a few months of conflict, Gladys left. But she returned to nurse Jeannie when she fell ill and eventually died.

Influence

Even though Gladys was told she could never learn the Chinese language, necessity made it possible. Gladys learned the country dialect from her customers so that she could share the gospel with them. Her stories about Jesus began to garner interest in the town too, so that large crowds would gather in the evening to hear the small woman speak. Even the mandarin of the town was interested and invited her for a meal. Not used to people standing up to him, she startled him by disagreeing with him about his religion. However, as he watched Gladys at her work, he was touched to see her take in abandoned children, as well as offering basic medical care to any who came to her. Eventually, he became a Christian.

Gladys appeared to be an unlikely candidate for mission work, but God chose her and gave her the determination to do the work.

By 1936, Gladys felt so much at home in Yangcheng that she decided to become a Chinese citizen. Pleased with this decision, the mandarin offered Gladys the job of foot inspector. Foot binding of young girls’ feet had been banned but not actively enforced, and Gladys was called upon to ensure the decree was being followed. Through this opportunity, she was allowed to visit every home and share the good news about Jesus. Gladys praised God as she tramped through the mountain passes to remote villages she had never visited before.

One day, the mandarin called on her to stop a prison riot. Gladys, only four foot ten inches, stepped into the prison and began to listen to the complaints of the criminals. When she saw the appalling conditions they lived in, she promised to ask the mandarin to improve them and find useful work for the prisoners to fill their days. Satisfied, the prisoners returned to their cells.

War with Japan broke out in 1938. At first, Yangcheng was not affected, but then the bombs began to fall nearby. By this point Gladys had accumulated one hundred abandoned or orphaned children, ranging from toddlers to teenagers. As the fighting moved closer, Gladys knew she would have to leave and get her children to safety. While she considered the best place to go, the Japanese closed the roads around the town. Having lost that escape route, Gladys looked to the mountain pathways, which she now knew well. The mandarin, pleased with her plan, offered her food supplies and soldiers as bodyguards for part of the way.

The twelve-day journey was difficult as the food ran out and the rough paths slowed the children down. However, God provided help along the way. A Buddhist priest allowed them to sleep in his temple one night. Another night, a group of Chinese soldiers fed and guarded them while they slept. But when they finally reached the Yellow River, Gladys broke down in tears. All the boats were gone. Some of her children came to her, asking her to ask God to part the waters for them as He had for the Israelites. Admonished, Gladys called her children together to pray and sing hymns. A Chinese officer heard the music and came to investigate. Hearing their story, the officer signaled for the boats to return, and Gladys and the children were taken to the other side. Gladys was ill by this time, and the rest of the journey by train passed in a blur. Finally arriving at Fefung, the children were placed with people to care for them. Gladys, ill with typhus, was sent to the hospital.

Final Days and Legacy

It took months for Gladys to recover. Still in a weakened state, she was flown home to London. When her health improved, she was able to take speaking engagements at various churches, telling them about the needs in China. But she was uncomfortable in Western culture and decided to return to China. When the Communists gained power in 1949, Gladys was forced to leave. She moved to Taiwan and established the Gladys Aylward Orphanage, taking in abandoned children. She worked with the poor and also founded the Gladys Aylward Children’s Home. She died at the age of sixty-seven in 1970.

Once Alan Burgess’ biography The Small Woman was published in 1957, Gladys Aylward became popular, much to her discomfort. Hollywood, too, publicized her through a movie called The Inn of the Sixth Happiness, a highly romanticized version of her journey through the mountains. Gladys appeared to be an unlikely candidate for mission work, but God chose her and gave her the determination to do the work.