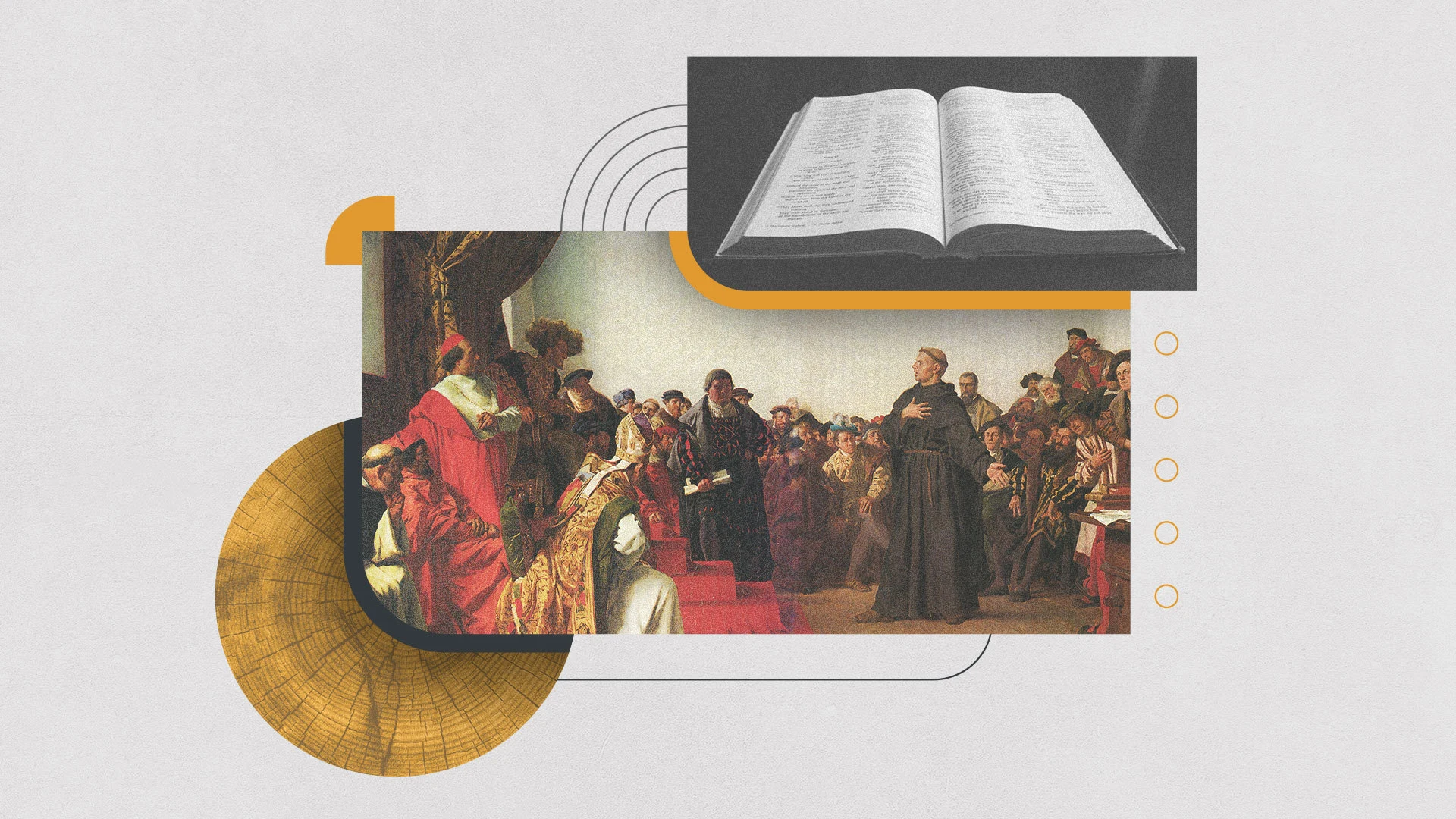

What do we mean when we say that we believe in sola Scriptura, or Scripture alone? Like all the solas, a proper understanding of the doctrine of sola Scriptura requires a certain amount of historical and theological context. In the first place, we need to understand that the Reformation doctrine of sola Scriptura arose within the context of the late medieval Western church and its teaching. It was a response to perceived errors in the teaching of the Church. So what was it that the Reformers found objectionable?

The dispute with the Church of Rome was not over the inspiration or inerrancy of Scripture. Rome affirmed both doctrines. Instead, the problem was that over the course of many centuries, Rome had gradually adopted a view of the relation between the church, Scripture, and tradition that effectively placed final authority somewhere other than the Word of God. Tradition was conceived of as a second source of revelation, and the pope and Roman magisterium (the collection of bishops) was viewed as the final authority in matters of faith and practice.

The Reformers wanted to call the church back to a view of the relation between Scripture and tradition that was found in the early church. They believed that the Bible itself taught such a view. The Reformation doctrine of sola scriptura, or the Reformation doctrine of the relation between Scripture and tradition, affirms that Scripture is to be understood as the sole source of divine revelation, the only inspired, infallible, final, and authoritative norm of faith and practice. What Scripture says, God says (2 Tim. 3:16). Scripture is to be interpreted in and by the church, and it is to be interpreted within the hermeneutical context of the rule of faith (Acts 15). All of this requires nuanced unpacking and explanation, and that is what the recommended books below do.

Among evangelicals, there is a common misunderstanding of sola Scriptura that views the Bible not only as the sole final authority but as the sole authority altogether. In other words, the church, the ecumenical creeds, and the confessions of faith, are largely dismissed even as secondary authorities. It is the "no creed but Christ" or "no creed but the Bible" attitude that is so prevalent in the evangelical church today. (Of course, those who assert such slogans fail to realize that a statement such as "No creed but Christ" is itself a creed—a statement of what one believes.)

Those who espouse this misunderstanding of the Reformation doctrine are often unaware that it was not the view of the early church and it was not the view of the magisterial Reformers. In fact, where one most often encounters this view historically is in the writings of various heretics (for example, the Arians of the early church, the Socinians of the sixteenth century, the anti-Trinitarians of the nineteenth century, and liberal theologians of the last two and a half centuries). This bad version of biblicism has been the source of innumerable false doctrines.

If we are to grasp anew the riches of the Reformation solas, we must begin with a solid and informed understanding of the doctrine of sola Scriptura. We must understand the doctrine itself as well as the erroneous views to which it stands opposed (both on the Roman Catholic side and on the "No Creed but Christ" side). The following books are a good place to begin studying the meaning and importance of this doctrine. It should be noted that most of these books are not light reading. The issues involved in the debates were and are complex, and they require serious and deep thinking. For those who need to dip their toes in the water before diving into the deeper works, the book Sola Scriptura, edited by Don Kistler, is a very helpful introduction.

William Whitaker, *Disputations on Holy Scripture

What John Owen's Death of Death in the Death of Christ is to the doctrine of effectual atonement, Whitaker's sixteenth century work is to the Reformed doctrine of Scripture. This is not easy reading, but it is worthwhile reading. It will reward the time and effort put into it.

Francis Turretin, Institutes of Elenctic Theology, Vol. 1.

Francis Turretin's work is a masterpiece of theological reflection, and his chapters on the doctrine of Scripture in volume 1 address the main points of contention between the Reformers and the Roman Catholics.

Peter Lillback and Richard Gaffin, eds. Thy Word Is Still Truth

This rather large work (1392 pages) is subtitled Essential Writings on the Doctrine of Scripture from the Reformation to Today. And that is what it is. The four selections found in part one are significant contributions by Martin Luther, Ulrich Zwingli, Heinrich Bullinger, and John Calvin on the doctrine of sola Scriptura. These provide much-needed historical context.

Keith A. Mathison, The Shape of Sola Scriptura

In my book, I attempt to trace the history of the doctrine and defend it against critics on both the Roman Catholic and evangelical sides.

Richard A. Muller, Post-Reformation Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2: Holy Scripture.

This work, while probably the most demanding of the five listed here, is very helpful for those willing to expend the effort. In this work, Muller looks at every aspect of the doctrine of sola Scriptura, from its context in the late fifteenth century to the detailed explanations of it found in the writings of the post-Reformation theologians.