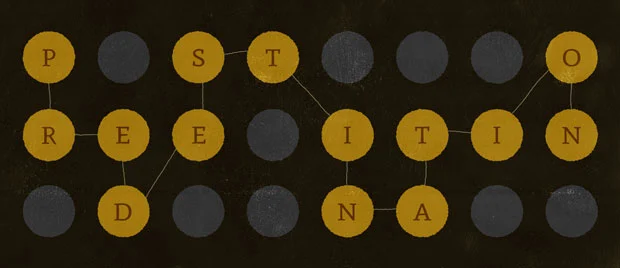

Should We Talk About Predestination?

I’d like to begin a series on—get ready—predestination. Yes, I said that word. I know this is not the most popular topic to bring up among polite company; in fact, it’s downright divisive, isn’t it? In the fifth century, Augustine recounted in his letters that some said, “The doctrine of predestination is an obstacle to the usefulness of preaching.” And who wants an obstacle? In the sixteenth century, John Calvin had to go out of his way to state that preachers should preach no less on the deity of the Son, the deity of the Holy Spirit, or the creation of the universe than on predestination.

Should we even talk or preach about predestination? Because predestination is a biblical doctrine, the answer is a resounding “Yes!” You see, without predestination, you would have no Bible. Abram was chosen out of Ur of the Chaldeans (Gen. 12). Israel was chosen out of all the nations of the earth (Deut. 4:37; 7:6–8; Ps. 105:6). A new Israelite remnant was chosen after their exile (Isa. 41:8–9; 42:1; 43:1–7; 44:1–2; 45:4). Jesus taught predestination (Matt. 11:25–27; 13:11–16; Mark 4:11–12; John 6:37, 66; 10:26–30; 14:1; 17:6, 9, 11–12). The Apostles taught predestination (Rom. 8:28–39; 9–11; Eph. 1; Phil. 1:6; 2:13; 1 Peter 2:5–10). Since predestination is a biblical doctrine, we must talk about it. The question is how?

Let me point you to a succinct answer. When theologians, pastors, and elders from throughout Europe gathered in the Dutch town of Dordrecht in 1618–1619 to deal with the Arminian controversy, they offered this statement:

“Just as, by God’s wise plan, this teaching concerning divine election has been proclaimed through the prophets, Christ himself, and the apostles, in Old and New Testament times, and has subsequently been committed to writing in the Holy Scriptures, so also today in God’s church, for which it was specifically intended, this teaching must be set forth—with a spirit of discretion, in a godly and holy manner, at the appropriate time and place, without inquisitive searching into the ways of the Most High. This must be done for the glory of God’s most holy name, and for the lively comfort of his people.” (Canons of Dort 1.14)

This blog post lays out the ground rules for how we must talk and preach about predestination as Christ’s witnesses in the world.

With Discernment

We must talk about predestination with discernment. When Paul penned Romans 9, he was writing to a Christian congregation made up of Jews and Gentiles in distinction from unbelieving Jews and Gentiles. Believing Jews were those of the promise while unbelieving Jews were those merely of the flesh (Rom. 9:3, 6–8). Paul used another illustration of this concept when he said that among the Jews there were those who were of the vast sand of ethnic Israel while there were also those who were of a small gathered remnant (Rom. 9:27).

This means that when you talk and preach about predestination, you must always keep in mind those you with whom you are speaking. Are you talking to unbelievers? If so, are they hard-hearted and scoffing at the doctrine, or do you discern the working of the Holy Spirit in their genuinely questioning the truth? Are you talking to a congregation of professing believers? If so, some may be strong in faith and able to plumb the depths and scale the heights of such a doctrine, while others may be weak in faith and the very mention of predestination will cause them doubts and worries. Are you talking to adults, with all the distinctions above, or are there also children in the audience? And while you are talking to such a congregation, keep in mind that there are those who genuinely believe, whether strongly or weakly, and that there may also be those who are merely pretending to believe, as hypocrites do.

With Reverence

We must also talk and preach about predestination with reverence. Paul talks reverently of predestination in Romans 9:20–21:

But who are you, O man, to answer back to God? Will what is molded say to its molder, ‘Why have you made me like this?’ Has the potter no right over the clay, to make out of the same lump one vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use?

This was the climax of Paul’s argument in Romans 9. Paul begins his argument by talking about the unbelief of the ancient covenant people, his fellow Jews (vv. 1–5). The first objection he addresses was whether God’s promise to Israel had failed (v. 6). But Paul says that ever since God began his promises to the patriarchs there was a distinction between those “descended from Israel” and those who truly “belong to Israel” (v. 6), between those who are merely Abraham’s outward children of the flesh and those who truly are children because they are Abraham’s offspring of the promise (vv. 7–8). Paul starts in history and then works his way back into eternity: “though they were not yet born and had done nothing either good or bad—in order that God’s purpose of election might continue, not because of works but because of him who calls” (v. 11).

The next objection is whether God is unjust because he chooses one and not another. Paul’s answer is, “By no means!” (v. 14) He doesn’t speculate but simply quotes Scripture (vv. 15–17), concluding that God “has mercy on whomever he wills, and he hardens whomever he wills” (Rom. v. 18).

But if this is true, then “why does he still find fault? For who can resist his will?” (v. 19) Do you hear the objection? It’s that predestination makes us robots since there’s nothing we can do about it. Paul doesn’t offer a philosophical response sorting out this conundrum. He asserts that God is God and we are not; he is the Creator and we are creatures; he is a potter and we are clay (vv. 20–21).

Because predestination is a topic shrouded in mystery as well as much misunderstanding, we should speak of it reverently as Paul did. Notice how Paul ends this entire section of Romans 9–11 by saying, “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!” (Rom. 11:33). In commenting on this passage John Calvin said that when we discuss God’s eternal counsel “we must always restrain both our language and manner of thinking, so that when we have spoken soberly and within the limits of the Word of God, our argument may finally end in an expression of astonishment.”

For God’s Glory

We must also talk of predestination in such a way that it is for God’s glory. “God has failed.” “God is unjust.” “God makes us robots.” Paul’s point in Romans 9 is that predestination solves these objections because it is ultimately for God’s glory, not our intellectual satisfaction. “Who are you, O man?” (v. 20) God is God. You are not. “Has the potter no right?” (v. 21) Absolutely he does. He glorifies Himself in His pottery, making “one vessel for honorable use and another for dishonorable use” (v. 21). Paul’s ultimate point is that God glorifies Himself in His works: “What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory” (vv. 22–23, emphasis mine).

When you talk or preach about predestination, are you doing so to bring him praise? “Blessed be the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, who has blessed us with every spiritual blessing in the heavenly places in Christ, even as he chose us in him before the foundation of the world” (Eph. 1:3–4). When you talk or preach about predestination, are you doing so to magnify His grace? “To the praise of his glorious grace” (v. 6). In fact, Paul repeats this doxology two more times in Ephesians 1:12 and 1:14 because God has poured out His extravagant grace upon His people. When you talk or preach about predestination, can your words be “translated” to say this: “For from him and through him and to him are all things. To him be glory forever. Amen” (Rom. 11:36).

For Our Comfort

Finally, we must talk of predestination in such a way that it is also for our comfort. What comfort does Romans 9 have for you, for the world, and for me? After starting with recorded redemptive history in the Old Testament, then tracing backward into eternity, Paul ends up placing the gospel right in our laps, in our own personal history: “even us whom he has called, not from the Jews only but also from the Gentiles?” (Rom. 9:24). Don’t accuse God of lying. Don’t accuse God of injustice. Don’t accuse God of making robots. Rather, believe.

But the objection people had and still have is that when we talk of predestination, it is only beneficial for those whom God “calls.” When you talk of predestination, it should always lead to the gospel: “Do you want to know that you have been called into God’s kingdom because he predestined you for that glory? Then believe in Jesus.” When we talk this way, we lead people to the joy of knowing that while they once were “not my [God’s] people,” God now calls them “my people” and “sons of the living God” (Rom. 9:25–26). As Martin Luther once wrote:

Follow the order of the Epistle to the Romans. Worry first about Christ and the gospel, that you may recognize your sins and his grace, and then fight your sin, as Paul teaches from the first to the eighth chapters. Then, when you come under the cross and suffering in the eighth chapters, this will teach you of foreknowledge in chapters 9, 10, and 11, and how comforting it is.

Yes, we should talk about predestination. We should talk about it in a way that leads sinners to Jesus Christ, which brings God eternal glory, and which brings God’s people eternal comfort.

This article is part of the Predestination collection.