One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church

“One nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty . . .” We say it. We argue about it (especially the “under God” part). But is it true? In reality, how united is the United States? The “more perfect union” sought by Lincoln is hardly perfect in terms of harmony. We are a nation—morally, philosophically, and religiously—deeply divided. Yet there remains the outward shell of formal and organizational unity. We have union without unity.

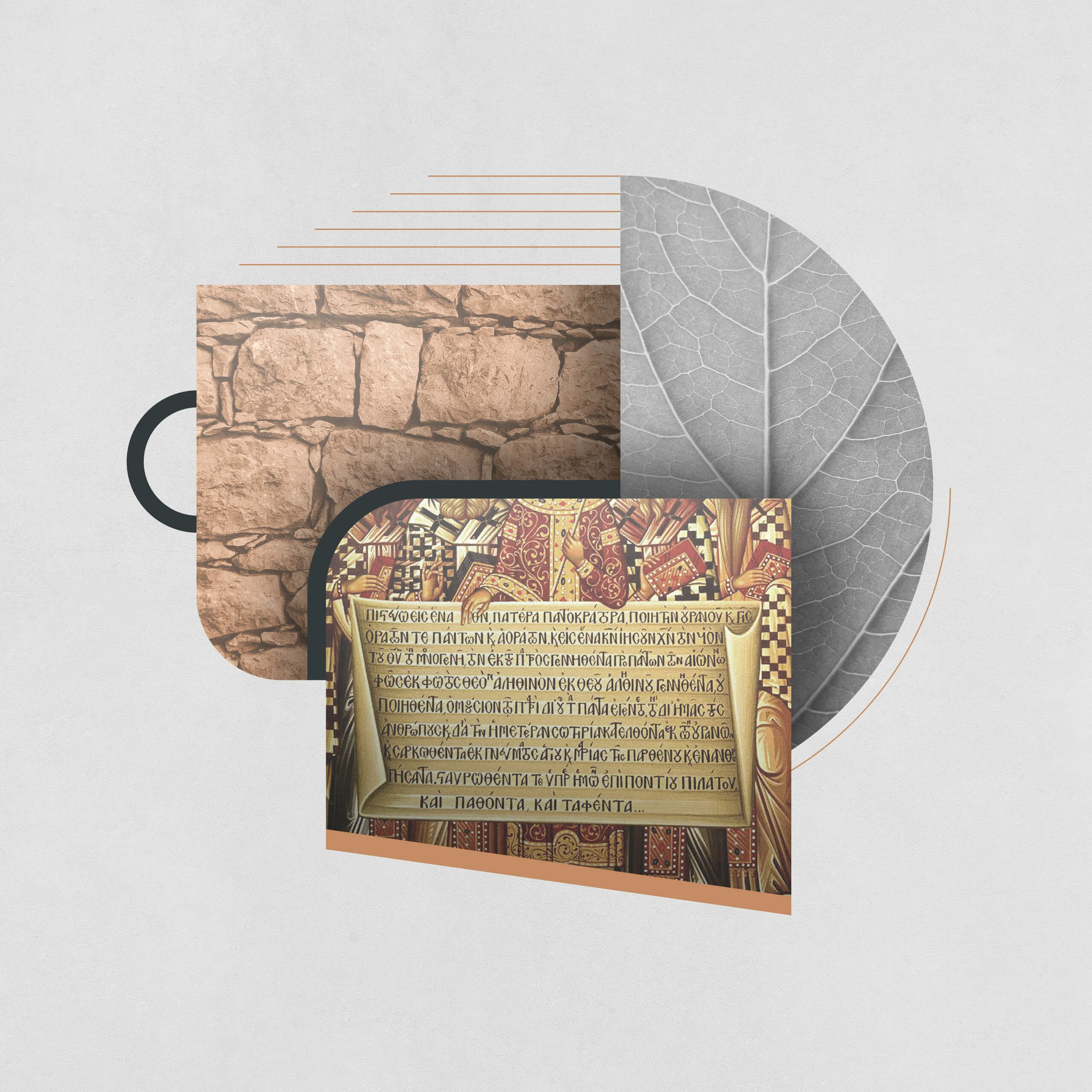

As it is with the “United” States, so it is with the unity of the Christian church. The “oneness” of the church is one of the classic four descriptive terms to define the church. According to the council at Nicaea (325 AD), the church is one, holy, catholic, and Apostolic.

Few church bodies today give much regard to being Apostolic. Fewer still seem concerned with the dimension of the holy. When these two qualities become irrelevant to the minds of church people, it is a mere chimera to speak of catholicity and unity.

The church, organizationally, is hopelessly fragmented. Since the birth of the “Ecumenical Movement,” the church has seen more splits than mergers. The crisis of disunity is on the front pages following the Episcopal church’s decision to consecrate a practicing, impenitent homosexual to the role of bishop.

Is unity a false hope? Is it, in its historic expressions, merely an illusion?

To answer these questions we must consider the nature of the unity of the church.

In the first instance, the deepest and most significant unity of the church is its spiritual unity. Though we can never separate the formal from the material with respect to the church’s unity, we can and must distinguish them.

It was Augustine who taught most deeply about the distinction between the visible church and the invisible church. With this classic distinction Augustine did not envision two separate ecclesiastical bodies, one apparent to the naked eye and another beyond the scope of visual perception. Now, did he envision one church that is “underground” and another one above ground, in full view?

No, he was describing a church within a church. Augustine took his cue from our Lord’s teaching that until He purifies His church in glory, it will continue in this world as a body that will include “tares” along with the “wheat.” The tares are weeds that grow along with the flowers in Christ’s garden.

Because of the presence of wheat and tares simultaneously in the church, we know that believers co-exist with unbelievers, the regenerate alongside the unregenerate. It was this situation that prompted Augustine to describe the church as a “mixed body” (corpus permixtum). The invisible church is the church made up of true believers. It is the church comprised of the regenerate, or as Augustine observed, the “elect.”

[pullquote]

Jesus made it clear that there are some, indeed many who profess faith but do not possess it. His piercing warning is the climax of the Sermon on the Mount:

Not everyone who says to Me, “Lord, Lord,” shall enter the kingdom of heaven, but he who does the will of My Father in heaven. Many will say to Me in that day, “Lord, Lord, have we not prophesied in Your name, cast out demons in Your name, and done many wonders in Your name?” And then I will declare to them, “I never knew you; depart from Me, you who practice lawlessness!” (Matt. 7:21–23, NKJV)

Elsewhere Jesus noted that people honored Him with their lips while their hearts were far from Him. The claim on the lips of the tares is that they labored for Christ. Yet Jesus will dismiss them. He will ask them (nay, command them) to leave. He will declare that they were never at any time part of His true church. “I never knew you.” These are not onetime sheep who became goats. They are the sons and daughters of Judas who were unbelievers from the beginning.

We notice also that Jesus said that the number of such self-proclaiming believers, who are not really regenerate, is declared to be “many.” This should elicit caution in our assumptions of the success of our methods and techniques of evangelism. We tend to be quite sanguine with our “evangelistic statistics” when we assume the conversion of all who answer an altar call, make a “decision for Christ,” or recite the “sinner’s prayer.” These tools can help measure outward professions, but they do not give us a glimpse into the heart. All we can ever see of a person’s profession is his fruit. And even the fruit can be deceptive. God, and God alone, can read the human heart. Our gaze cannot penetrate beyond the outward appearance.

Augustine also maintained that the invisible church exists substantially within the visible church. There may be rare instances when a true believer never connects with a visible church if providentially hindered. The thief on the cross never had the opportunity to attend new member classes in a local church.

However, for the most part, the true members of Christ’s invisible church are found within the visible church. Though the visible church a truly regenerate person may belong to differs from the church another regenerate person belongs to, the two believers are, in reality, already united in the one true, invisible church.

The union of believers is grounded in the mystical union of Christ and His church. The Bible speaks of a twoway transaction that occurs when a person is regenerated. Every converted person becomes “in Christ” at the same time Christ enters into the believer. If I am in Christ and you are in Christ, and if He is in us, then we experience a profound unity in Christ.

The High Priestly Prayer of Jesus in John 17 in behalf of the unity of His followers was not a failure or unfulfilled plea. God has been pleased to ensure a unity among believers that, though invisible, is nevertheless real. It is a common bond grounded in one Lord, one faith, and one baptism.