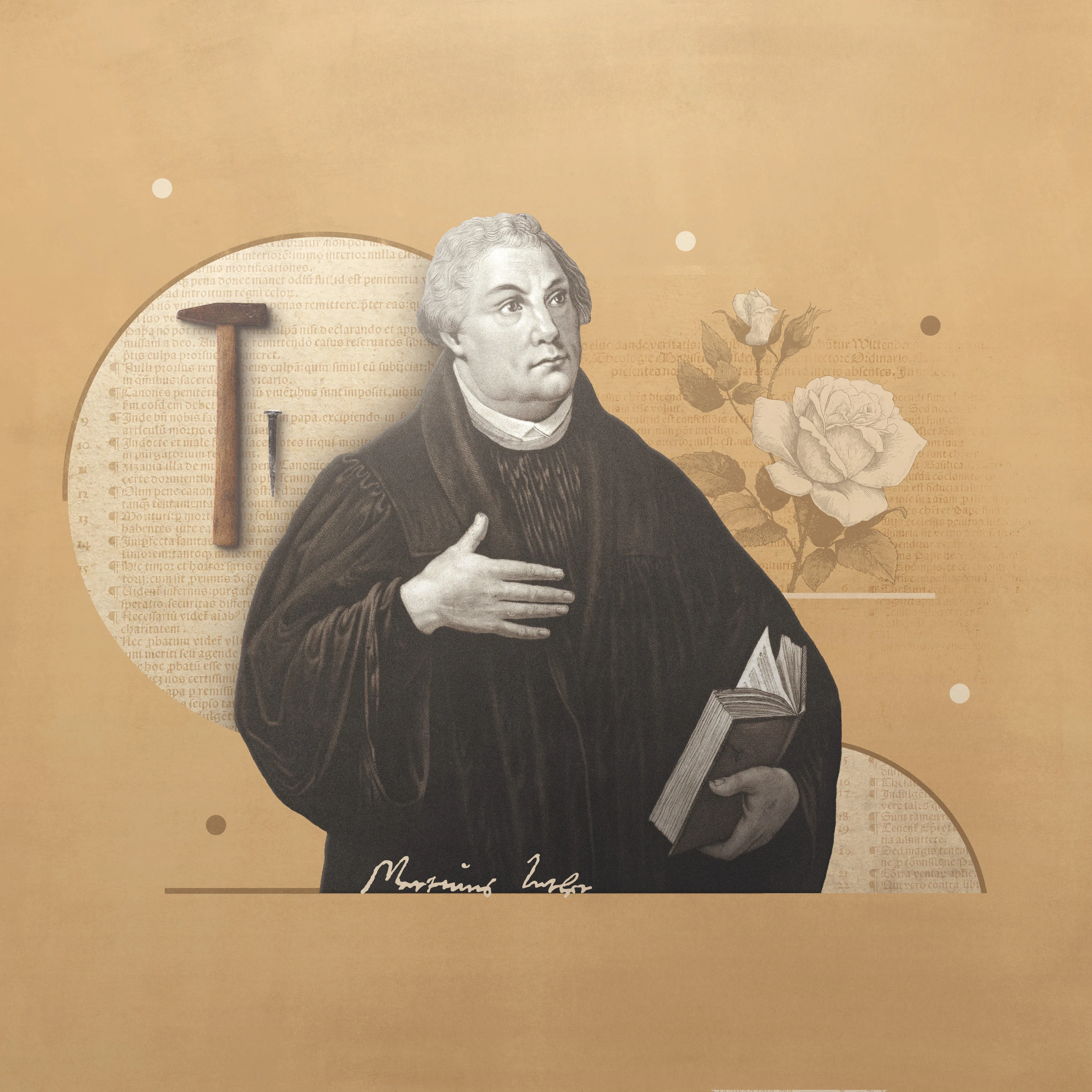

Who Was Martin Luther?

As a doctoral student, Martin Luther finally had access to the university library. Here, for the first time in his life, he held a complete Bible in his hands.

The Bible was venerated in the medieval church, and portions of it were read from the lectionary used in worship services. But Bibles had to be copied by hand, so they were very expensive. Many churches did not even own one. And if they did, most people were illiterate, so they could not read it anyway.

No wonder the church had drifted from the Word of God. Yes, the medieval church taught that Jesus died for our sins, a salvation applied at baptism. But if you sinned after that, you had to pay. Each sin that you confessed before a priest could be forgiven, as long as you performed some kind of penance. Even forgiven sins, though, required a temporal punishment, if not in this life, then in purgatory. In the meantime, to be saved, a Christian needed to accumulate enough merit through good works and acts of devotion in order to deserve God’s grace and to earn a place in heaven.

Young Luther was no rebel. He took the church’s teaching seriously. Church vocations, with their vows of celibacy and other ascetic disciplines, were thought to be more spiritual and more likely to lead to heaven than the worldly lives of the laity. So Luther became a monk, then a priest. Still, he would agonize over his sins. Once he had access to a Bible, he read it voraciously, and a new picture of God, of Christ, and of salvation started to become clear.

The University of Wittenberg was one of the new Renaissance schools that stressed going back to the original sources. The medieval universities taught theology through the method known as scholasticism, using authoritative textbooks and rationalistic disputations. But the original source for Christianity is the Bible. And since Renaissance-style, classical education also taught Greek and Hebrew, it became possible to study the Bible in its original languages, whereas previously it had only been available in a Latin translation. When Luther earned his doctorate, the university put him on faculty and gave him the responsibility of teaching the Bible.

In preparing a lecture on the book of Romans, Luther struggled to understand this passage: “The righteous shall live by faith” (Rom. 1:17). Suddenly it hit him: We are justified by grace through faith in the atoning work of Jesus Christ! Luther said, “Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates.”

Meanwhile, it became clearer that the medieval church thought otherwise. It was sponsoring a sale, promising to release Christians from purgatory if they would buy a certificate called an indulgence. People had been taught that they would suffer in penitential fire for seven years for every sin they committed, including those that had been forgiven. Christians were expecting to be in purgatory for thousands of years before they could enter heaven. Of course, they gladly bought indulgences.

Here I felt that I was altogether born again and had entered paradise itself through open gates.

For Luther, not only was this a cynical scam that exploited the poor (an indulgence cost workers about a week’s wages), it was a monstrous violation of God’s saving Word.

On October 31, 1517, Luther nailed to the church door a list of Ninety-Five Theses against the sale of indulgences, which he was willing to debate. Someone, using the newly invented printing press, printed hundreds of copies. Someone else translated them from scholarly Latin into popular German, selling thousands. They soon spread through all of Germany. They were then translated into French, Italian, and English. The Ninety-Five Theses, as we would say today, went viral.

The Vatican responded with treatises of its own, which Luther answered. The controversy escalated into other issues. Luther said that the Bible gives no support for indulgences. The Vatican replied that they are authorized by the pope. Luther responded that the Bible is a higher authority than the pope. The Vatican asked Luther how people could escape punishment for their sins and get to heaven without indulgences. Luther answered that Christians are justified by faith alone in Jesus Christ.

The pope excommunicated Luther. Notice that Luther didn’t “break away” from the Roman Catholic Church or “start his own church,” as is often said. He was trying to reform the church by bringing it back to its foundational gospel. For that, he was cast out.

Luther went on to translate the Bible into the language of the people, whereupon the Bible spread like wildfire. He then opened schools to teach people—including peasants, women, and everyone who wanted to learn—to read it.

He taught the doctrine of vocation—that farmers, craftsmen, husbands, wives, and parents all belong to “holy orders,” no less than priests and nuns—and that God Himself works through them as they love and serve their neighbors in their various callings. Luther himself got married and, with his wife, Katie, and their children, offered a model of the Christian family.

Luther would deal with many other issues, from “enthusiasts” who believed God spoke to them directly apart from God’s Word (which, to Luther, was exactly what the pope claimed) to other Reformers who believed Luther did not go far enough in reforming the church. Whenever he was thanked for launching the Reformation, Luther would deflect the praise. “I did nothing,” he would say. “The Word did everything.”